Laura Poitras Citizenfour makes its way to American soil just in time for the New York Film Festival

A little over a year ago when it was revealed that the government was on our cell phones, computers and basically under the crevices of everything that lit up, left some indifferent—didn’t you always kind of figure this was happening? Yet with proclamations of this magnitude and the prevalence of social media, like an Ebola virus seeping into our pores, privacy may be a thing of the past. Although questions of privacy and ethics surrounding “the safety of the American people,” remain significant, filmmaker Laura Poitras isn’t interested in debating them.

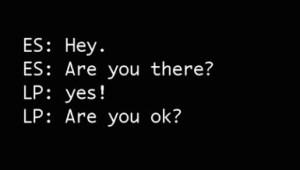

As her camera leads us through the tunnels of Hong Kong, Poitras begins by reading a string of emails sent to her by “Citizenfour.” Privacy and discretion are specified, but little else. She is directed to meet Citizenfour in a hotel lobby where he will be sitting. As Poitras sets up her camera equipment in a hotel room it is revealed that Citizenfour is a young unassuming man, perhaps in his mid to late twenties. He is wearing glasses and a white undershirt, not so much camera ready as ready to give directives.

Glenn Greenwald a journalist from The Guardian, who accompanies Poitras to the meeting, suggests to start with background information, but little is given. Besides where he grew up and the position which he currently holds (or held) at Booz Allen Hamilton as an infrastructure analyst, little else is divulged, emphasizing that the information he is about to leak should be highlighted, not his personal life. After scribbling on his notepad Greenwald’s collogue Ewen MacAskil, stalls for a moment, “sorry I don’t know your name?”

“Oh a sorry, I a, my name is Edward Snowden. I go by Ed.”

We know his face and are familiar with his purpose, supplying the American people with classified information pertaining to issues of privacy, but Poitras’ agenda is not pointed in a distinct direction, documenting events as they take place, rather than strategically placing talking heads in-between each scene. As she explained during the New York Film Festival’s “Director’s Dialogue,” after the film’s world premiere, Poitras is not interested in a political statement, but in the nuance of behavior when confronted with “basic human drama.”

“I am really interested in understanding the human consequences and how people confront conflict and risk [and] in implicating the audience on an emotional level. I am really committed to creating primary documents, I am not interested in what people think about things, I am interested in how people act.”

In a style referred to as Cinema Vérité (truthful cinema), which does not often find itself in documentaries pertaining to secrets, Poitras masterfully coveys her subject. In a time of media saturation, it’s a relief to see someone simply being. Yet unnerving as the close-ups reveal the redness in Snowden’s face and blemishes on his skin. After taking a shower Snowden is styling his hair in the mirror with gel and having some trouble. We are not sure if discretion concerning which hair style to sport have to do with vanity or being recognized? As he shaves his goatee and works out several hairstyles, seemingly forgetting that the camera is in the room, one can’ t help but feel like a voyeur as he contemplates his next steps in a peculiar zen-like state: prison, asylum, death?

Although the T.V. in his hotel room is showing his mug on a loop, Snowden is disinterested, focusing on his girlfriend who is back in Hawaii, unaware of events until just now. Yet the films pulse begins to race once the camera focuses off of Snowden (Poitras wanted to film Snowden while he was confined at the Moscow airport, but this was too risky) and onto the media process in a time of heightened security. This focus is centered on Greenwald, a journalist of several accomplishments including fluency in Protégées, a Law degree from NYU, and a steadfast commitment to journalism, which leads to his partner’s detainment at Heathrow airport in London.

Throughout the process of filming, Poitras has made three documentaries dedicated to the product of America’s War on Terror, including “My Country, My Country” and “The Oath,” Poitras has had an interesting relationship with the United States government since, including finding herself on a list the government claims does not exist, causing her to live in Germany. As George Packer’s recent New Yorker article reveals, much of Poitras’ source material for the film was heavily guarded and the editing process was completed in Germany:

“They worked on computers with high levels of encryption, memorized extremely long passwords that were frequently changed, left their phones outside, and shut the windows in rooms where sensitive conversations took place. They were compressing ten weeks of work into less than a month, in time for the première.”

As Poitras came to the stage after the films standing ovation at Lincoln Center, she did so with a bit of stagger and shake in her voice, completely off struck by the response and perhaps the fact she had made it to her place of birth, body and footage unscathed.

Although the film does not answer questions which are customary to documentary films, it does present the visual clarification that is necessary to stop indifference—a man, a kid really, willing to sacrifice his wellbeing in order to provide information—is a startling thing and something that each audience member can come to terms with in their own space and time. I may be able to stock up on contact solution, toilet paper, and a 6 liter bottle of Belvedere vodka anytime I want, but it might be for my bunker instead of my apartment.

Director’s Dialogue, Lincoln Center