Christopher Nolan’s stunning epic reminds us that genius is no guarantee of wisdom

By Michelle Montgomery

Julius Seligmann Oppenheimer was born in Hanau, Germany and moved to the United States as a teenager in 1888 where he began work in the textile industry sorting rolls of cloth for his cousins burgeoning suit lining business. Julius knew no English but had a passion for fabrics and color. As the century came to a close, he became a partner at Rothfield, Stern & Company. Julius moved his family to a large apartment on Riverside Drive which occupied the entire floor and overlooked the Hudson River. The family collected art, owned a summer home (which included a dock for Julius’ 40-foot sailing yacht) and joined the Ethical Cultural Society instead of a synagogue. [1] Assimilating into American culture was a goal for many German Jews who started the reform movement as a means to worship and walk in the world unencumbered by judgment. Growing up amongst Picasso paintings, chauffeurs and live-in maids, Julius’ son Robert knew that his purpose was accomplishment and once his genius became known to him and the world, accomplishment was exchanged for assassin.

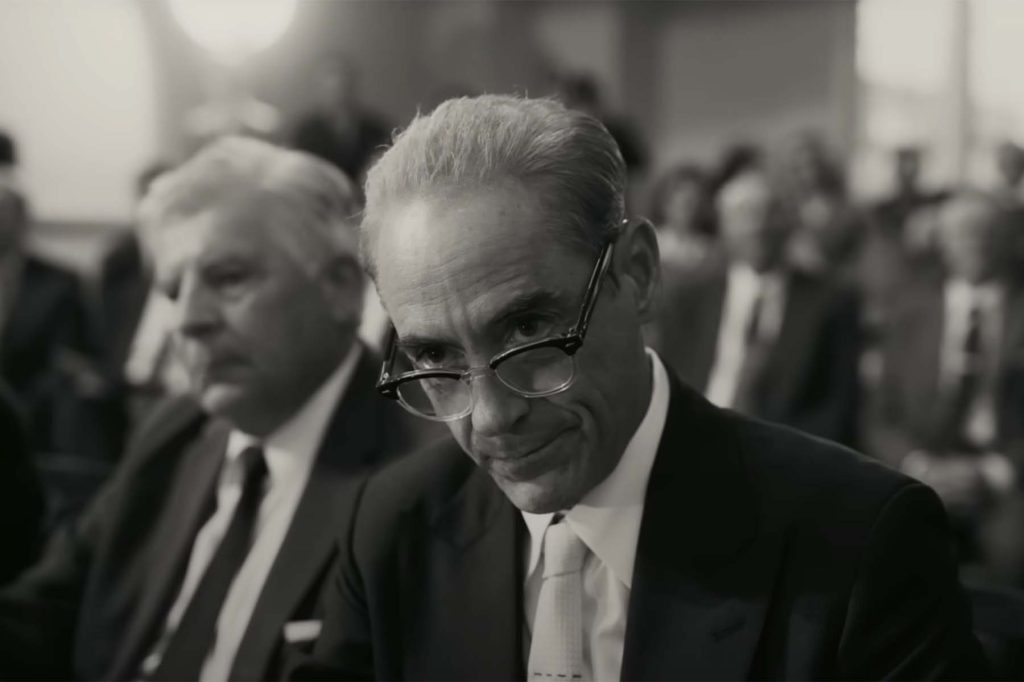

Christopher Nolan’s Film Oppenheimer, which is based on the book “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer” accounts Robert’s (Cillian Murphy) trials regarding his communist leanings and security clearance after the Manhattan Project in which Robert was the driving force behind the creation of the atomic bomb. Through these trials (and the hearing of a colleague Lewis Strauss, played by Robert Downey Jr.) Robert’s life and his creation are chronicled. Essentially the film is a dick measuring contest; a dance of men at tables with other men making judgments about each other and discussing security, extra marital affairs, communism and sometimes the bomb itself.

Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr)

After studying at Cambridge and the University of Göttingen in Germany Robert became so intrigued by quantum physics that he brought the “new science” to the University of California at Berkeley. Robert’s time at Berkeley proved productive in more ways than one; he met colleagues who were members of the communist party, established his psychics lab with some of the brightest minds in the world, served many a cocktail at his home and began courting Jean Tadlock (Florence Pugh) a young medical student who was studying psychiatry. Jean was a communist (who according to the film) bonded with Robert over the “Bhagavad Gita,” good sex and by ‘playing’ hard to get.

The women in Robert’s life are flawed to the point of alcohol abuse and suicide which may be a testament to his decision-making skills. Robert would meet his wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) when she was still married, and they would carry out their affair unapologetically out in the open. [2] As Strauss points out in the beginning of the film “genius is no guarantee of wisdom” and Robert (who was also lacking in the lab) seemed to lack the wisdom necessary in order to sustain a healthy partnership. One could surmise that Robert joined the communist party ‘to get laid’ and that he joined his ex-girlfriend Jean Tatlock in San Francisco hotel room in order to feel wanted and desired. Robert would also start a 20 year-affair with Ruth Tolman (a clinical psychologist and wife of his colleague Richard Tolman) as a means of escape from his tumultuous marriage.

These relationships would have immense consequences for Robert and his dedication to his work (and to the bomb) often masked the tumult in his marriage. Nolan washes over much of these relationships as it seems that he (and the authors) main purpose was to examine their idol. Unlike Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (which was released the same day as Oppenheimer to acclaim and the number one spot at the box office) women are not the center here. We get a sliver of a feminist moment when Harvard graduate and physicist Lilli Hornig (asked to become a secretary for the Manhattan Project) reminds Robert that “they didn’t teach typing” at Harvard’s PHD Program. Nolan’s plot is far more focused on the men outwitting each other than the woman who were supporting and creating for them.

Jean Tadlock (Florence Pugh) sitting with Robert in the infamous San Fransisco hotel room

Oppenheimer is Nolan’s most plot driven film since Momento as it weaves several of Robert’s memories over a 40-year time-period while attempting to diagnose what propelled Robert to create the Atomic Bomb and its sprawling campus across the New Mexico desert. Robert would continue with the bomb despite Hitler ending his life in 1945 which seemingly ended WWII. The film and the book also attempt to capture why Robert (after being accused of several un-American activities by the US Government for most of his career) continued to work for an entity that was against him via the General Advisory Committee (GAC) where he attempted to drive (or at least steer) nuclear policy. Nolan drives his plot through flashbacks, countless cameos and via his spectacular use of technical filmmaking, which is his and the films strength. The scene’s featuring Strauss are shot in black and white while the A-bomb scenes propel sound as a tangential blast of radiating light. Nolan and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema shot Oppenheimer with 70 MM IMAX film, giving the film a maximum effect where it seems that Nolan’s main cinematic mission is to get his explosion just right. When it came time to shoot the actual bomb scene Nolan created his own bomb as opposed to relying on CGI.

The film’s magic comes from its craftsmanship which is shot with distinct purpose and style. Purpose and style also come through in Murphy’s performance and it’s safe to assume that no one else could master the role of Robert Oppenheimer; with Murphy’s piercing blue eyes, small frame, and direct tone he embodies Robert in form and function. The film becomes problematic (like the bomb itself) once the aftermath comes into play. Robert makes a speech, feels bad and at one point the death toll is discussed but the atrocities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are never shown and are only discussed as an aside. This is perhaps because Nolan wanted to focus on the man at hand, but you can’t really do that without discussing what that man’s ego (or lack of) made possible.

According to the atomic archive the entire death toll for Nagasaki and Hiroshima was estimated at 199,000 where the entire pre-raid population was at 450,000:

Aerial surveys revealed at least 60% of the city’s “built-up areas” were destroyed, leading to the conclusion that perhaps “as many as 200,000 of Hiroshima’s 340,000 residents perished or were injured,” as one United Press story put it. The same story quoted “unofficial American sources” that estimated that the “dead and wounded” might exceed 100,000.[3]

Pre and post Hiroshima courtesy of The Atlantic

Several of the victims had thought they escaped death only to die of radiation poisoning several days later. Nagasaki and Hiroshima were not small villages but burgeoning cities of industry. This is not something that a quote from the “Bhagavad Gita,” or a man’s shame can reconcile. Although Nolan’s attempt to uncover the why behind the behavior was successful, he made little attempt at uncovering the human tole and tragedy that was done as result of the weapon.

Robert would only write five scientific papers after the Manhattan Project as his main objective was to direct US policy towards ending more advanced weapons from entering the fray of weapons of mass destruction.[4] It could also be that science lost its sense of wonder for him once it was used as a weapon. Robert’s policy work with the GAC seemed to be his peace treaty moment where he wanted to manipulate the narrative towards less destruction, but this isn’t what happens. Instead, Robert becomes consumed by getting his security clearance back in order to be a part of the conversation, to avoid being the idle man with no direction. Although Men would indeed listen Robert’s ideas, they would do so as a means to weaponize them.

[1] [Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8. OCLC 56753298.]

[2] [Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8. OCLC 56753298.]

[3] (https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/documents/med/med_chp10.html)

[4] [Bird, Kai; Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41202-8. OCLC 56753298.]