In Martin Scorcese’s epic renderings of one of our nation’s darkest hours, he reminds us that in looking for our heart’s desire we needn’t look any further than our own backyard.

By Michelle Montgomery

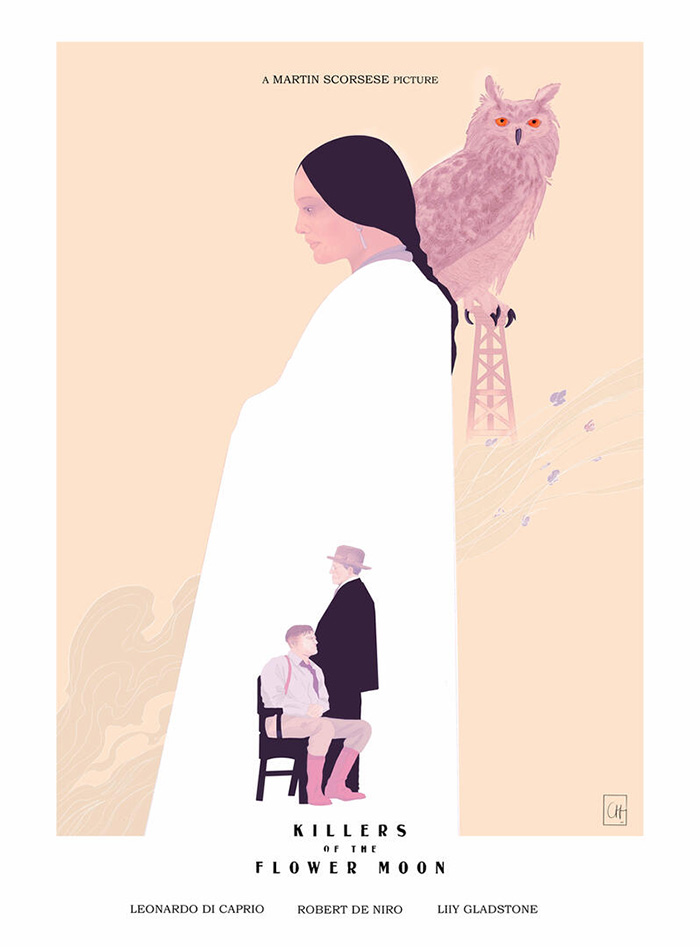

Art By Conor Fenner-Toora

In David Grann’s book “Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI” he begins by describing “the millions of tiny flowers spread over the blackjack hills and vast prairies in the Osage Territory of Oklahoma where a “galaxy of petals makes it look as if the gods had left confetti.” Grann then discerns that “In May, when coyotes howl beneath an unnervingly large moon, taller plants, such as spiderworts and black-eyed Susans, begin to creep over the tinier blooms, stealing their light and water. The necks of the smaller flowers break and their petals flutter away, and before long they are buried underground. This is why the Osage Indians refer to May as the time of the flower-killing moon. 1

As if plucked from the Old Testament, Grann’s book goes on to detail one of the most harrowing events in US history where white settlers managed to control and stake claim on Osage oil money at any cost. Grann centers his story around ‘a Hangman’s Son,’ Tom White, a former Texas Ranger turned Federal Agent for the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) who investigated the crimes committed against the Osage Indians. Grann describes Tom’s childhood “as if the Scripture were unfolding before his eyes: good and evil, redemption and damnation” where his father served as County Sheriff and executioner at the County Jail in Austin Texas.

Tom would grow up on jail property where he would watch his father Emmett interact with men charged with murder, arson, rape, burglary, and those who were “classified as lunatics.” Tom’s father (although firm) was known as “hardworking and pious” and treated every prisoner with respect and dignity despite violent acts that were directed towards him and almost took his life. Certain well-behaved prisoners would stay with Emmett and his children and do odd jobs around the house as Emmett was widowed when Tom was 6 years old.

Jesse Plemmons as Tom White

In Martin Scorsese’s film adaptation, he sidelines Tom White (played with beautiful ease by Jesse Plemmons) until more than halfway through his four-hour epic, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” making betrayal his film’s primary ingredient. After the lights dim and our creator greets us with a short message about the importance of seeing this film in the theater, we see the sun beaming through a wooded tent framing the Osage Chief’s hands while he holds up a traditional Osage pipe as if to hold up a sacrifice to the old way of life and to accept what is in store with open arms. A child’s hands glide across the outside of the tent so that he can see the elders inside as they contemplate their new future.

“The children outside listening . . . they will learn another language. They will be taught by white people. They will learn new ways, new ideas . . . and will not know our ways.”

After the ceremony, the elders bury the pipe as if to place it in a time capsule. As a means to reconcile with a past and accept a future of wealth with the knowledge that great fortune will not empower the Osage Tribe but will ultimately take power over them. The Osage recognizes that to be prepared for what is coming and to understand the true nature of man is one of the hallmarks of faith. Once the pipe has been buried the film cuts to a bubbling up hole of oil that bursts into the sky as the Osage Natives bathe in its riches. While the Osage dance in the wet goo to Robbie Robertson’s rockin’ score (met with the merging of pounding drums and a pulsing electric guitar) we watch as a montage of native wealth delights and beguiles us. The Osage are introduced to us as “the chosen people of chance. The richest people per capita on earth.”

The native woman prance through town with furs, jewels, newly polished model T’s, and white husbands who brag of “full blooded” wives. Scorsese centers his story on Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) who arrives in Osage by train with rotted teeth and a torn-up gut. Earnest is a simple man who “can read” and likes “all kinds of women.” By focusing on Ernest Scorsese is creating a narrative based on the coyote, not the righteous.

Earnest has just returned from WWI where he saw more men”die from the flu” than on the battlefield and in terms of what is next for him, Earnest is at the mercy of his uncle William “King” Hale (Robert De Niro). Hale owns a cattle ranch, is a reserve deputy sheriff, has good whiskey, is a good dresser, knows the native Osage tongue, and is a respected businessman by the Osage Tribe and the white man alike. For Earnest Hale is the ticket to a life filled with promise, until he meets Molly Kyle (Lily Gladstone), a full-blooded Osage Native with oil head rights.

When Molly meets Ernest she recognizes his intentions from the very start and calls him a “show-me-kah-see” (coyote) after their first meal together. She knows who he is and what his priorities are, yet allows him into her world despite this. Molly becomes enchanted with his looks and flirtatious humor all the while recognizing his true nature. Perhaps the most tragic aspect of this love story is that despite Earnest’s intentions he does love his wife; betrayal and love sit beside each other creating a brew of poison.

Lily Gladstone as Molly and Leonardo DiCaprio as Ernest

After Molly and Ernest Marry, the once quiet home that she shared with her mother has suddenly become the house of mooches with beds in the dining room and Ernest’s Family trying to guess which of their children is the whitest while servants wait on them. Ernest now shows up to the Saloon in polished cowboy boots and fine suits, he was made for this life yet wasn’t completely satisfied. Despite his new wife and children and the riches they came to bear, Hale wants more and has a solid grip on his nephew. Ernest (with no substantial goals other than pleasing his Uncle) is like a lost rat in the sewer, scavenging from tunnel to tunnel for the next crumb. Ernest and Hale’s greed begins to take hold of them and Hale’s status in the town gives him the illusion that anything he is up to can be bought and sold. This mentality works for Hale until it doesn’t.

After the death of her sisters Minnie, Anna, and Rita Molly assembles Private Investigators and even takes the train to Washington DC to inform the President himself about the unusual string of murders in their territory. As Grann’s book describes this tactic only worked because the newly formed BOI needed to dig itself out of a scandal:

“In 1924, after a congressional committee revealed that the oil baron Harry Sinclair had bribed the secretary of the interior Albert Fall to drill in the Teapot Dome federal petroleum reserve—the name that would forever be associated with the scandal—the ensuing investigation lay bare just how rotten the system of justice was in the United States. When Congress began looking into the Justice Department, Burns and the attorney general used all their power, all the tools of law enforcement, to thwart the inquiry and obstruct justice. Members of Congress were shadowed. Their offices were broken into and their phones tapped. One senator denounced the various “illegal plots, counterplots, espionage, decoys, dictographs” that were being used not to “detect and prosecute crime but…to shield profiteers, bribe takers and favorites.” 2

The Bureau’s newly appointed head J. Edgar Hoover needed a case for the Bureau to sink its teeth into and to show the Nation that pious good-natured men run the federal government, as opposed to the wild lawmen of the West. The United States was still trying to find its identity and its conscience.

Once Tom White was given the case of the Osage Indians he would assemble a diverse group of men to unravel why so many Osage were dying under unusual circumstances. In the early days of the Bureau (although Hoover would demand a strict dress code of dark suits and polished shoes) uniformity was not standardized yet in terms of how to build a case. Tom’s strategy was to find agents from around the nation who could blend their own individual talents and cultures into the case. Tom was to be the face of the case while the rest of the agents worked undercover. Despite Hoover’s practice of hiring clean-cut college boys, he took an exception with this case, giving White full reign at hiring the best candidates from around the country:

White brought in the singular John Wren. A one time spy for the revolutionary leaders in Mexico, Wren was a rarity in the bureau: an American Indian. (Quite possibly, he was the only one.) Wren was part Ute—a tribe that had flourished in what is today Colorado and Utah—and he had a twirled mustache and black eyes. He was a gifted investigator, but he’d recently washed out of the bureau for failing to file reports and meet regulations. A special agent in charge had said of him with exasperation, “He is exceedingly skilled in handling cases, and some of his work can only be described as brilliant. But of what avail are many nights and days of hard application to duty if the results are not embodied in written reports? 3

In the film, John Wren is played by Tatanka Means (a Native American of Oglala Lakota, Omaha, Yankton Dakota, and Diné descent) who is the man that finds Molly in a wasted state after being drugged with her own poisonous insulin. As he finds Molly in bed the disgust on his face speaks in generations of evil deeds.4

“Killers of the Flower Moon” was released to theaters on October 20th 13 days after Israel declared war against Hamas and a month before the US Holiday of Thanksgiving in which we celebrate with native foods the coming together of two cultures, the native Wampanoag people and 53 survivors of the Mayflower, or at least that’s the idea . . .

Rhetoric around colonialism and Zionism has recently sparked debate about how to manage populations that have succumbed to past and present genocide. Yet when we look to other nations in an attempt to understand our own, we can get lost in this rhetoric. It’s interesting what happens when a filmmaker looks no further than his own backyard to understand why humanity kills each other, but not without backlash. Some critics and influencers have accused Scorsese of cultural appropriation and have made the case that a Native film director should have made the film.

However this is not just a tale about the Native Osage, but a rendering of how the white man’s insecurities and fears enabled him to pursue deadly acts. Scorsese (who was an asthmatic child) often spent his days observing his neighborhood “Little Italy” on the Lower East Side where he lived with his parents and grandparents. Known for its rows of tenement houses and local law enforcement who “did not wear badges,” the neighborhood became “an atmosphere of fear” for young Marty who rarely left his family’s cramped apartment. Like Tom White, Scorsese saw “Scripture unfolding before his eyes” and several of his films would focus on men without badges surviving in unconventional ways. 5

“Killers of the Flower Moon” is now available on Apple + to stream and includes behind-the-scenes content where Scorcese and Osage Chief Geoffrey M. Standing Bear discuss the care in which Scorsese went to make this film. The director filmed in Osage County and utilized the men and women of the tribe for costume design, and props and to teach the actors their native Osage language. De Niro was described as being the best student whose preacher-like orations give us a nastiness not seen since “Cape Fear ” and “This Boy’s Life” (in which Dicaprio plays his forlorn adopted son). Lily Gladstone and Dicaprio also bring an exceptional amount of life to their characters and without culturally appropriate casting the film would have no life.

Martin Scorsese and Lily Gladstone

It’s clear in his film that Scorsese comes with a sense of purpose and understanding and makes known that his primary goal was to create an atmosphere of truth. By focusing on Ernest and not White or the FBI (Scorsese has already made a film about Hoover) he was able to focus his film on the dangerousness of romantic love and how its chemical components can drive us away from our dreams and blind us from what is right in front of us.

Molly feels fear all around her and her body and mind are in overdrive. While she has searched far and wide for the culprit perhaps if she too looked into her own backyard, all that she needed to know was right beside her. It’s important to also point out that like many women of her day and all days, not only was Molly deceived but she was also loved by her husband. This type of devotion (the building up and tearing down) is maddening and takes a psychological toll on her. As Molly joins her tribe (with Ernest and Hale beside her) in the wooded tent to discuss the murders, the Osage Chief reminds them of the sins of the past:

“When we left Missouri we didn’t even leave our dead babies. We laid them down and we rode our warriors over um to tell everyone that we will never leave this place again or will die here until the last one [. . .] You have something it wants. It didn’t want you when we was coming through genocide out coming home [. . .] That Osage is dying by the enemy. Do not let them die alone [. . .] we never prayed for the great life, we just prayed for life.”

Dissatisfaction ultimately comes from the scavengers who have no direction or at least follow a path with very few hills and valleys as if to make it to the mountaintop without the journey. Earnest and Hale want all the riches (and although they feel they may have earned these riches) what they get left with is an abundance of resentment.

Scorsese ends his film with a circa 1940s Lucky Strike Radio Show with strange gadgets creating sound effects and actors reading from scripts to a live studio audience. The Auteur leaves us with himself narrating the Obituary of “Mrs. Molly Cobb, 50 years of age passed away at 11 o’clock Wednesday night at her home. She was a full-blood Osage. She was buried in the Old Cemetery in Grey Horse beside her father, her mother, her sisters, and her daughter.” He goes on to say as he looks up at his studio audience “There was no mention of the murders.”

What Grann did and what Scorsese did (in their own particular way) was to make mention of the murders and both did so on a grand scale to ensure that what happened will never be forgotten.

- [Grann, David (2017). Killers of the Flower Moon: the Osage murders and the birth of the FBI (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-385-53424-6. OCLC 953738449.] ↩︎

- [Grann, David (2017). Killers of the Flower Moon: the Osage murders and the birth of the FBI (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-385-53424-6. OCLC 953738449.] ↩︎

- [Grann, David (2017). Killers of the Flower Moon: the Osage murders and the birth of the FBI (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-385-53424-6. OCLC 953738449.] ↩︎

- [Montoya, Isaiah (July 9, 2010). “Native actor sees success in film.” Navajo Times. Window Rock, Arizona. Retrieved October 2, 2019.] ↩︎

- [“Martin Scorsese Biography”. National Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.] ↩︎